Connected devices are rapidly being adopted by cities, in the workplace, and in the home. While they offer efficiency and convenience, these smart things present a very broad new set of security, privacy, and safety challenges.

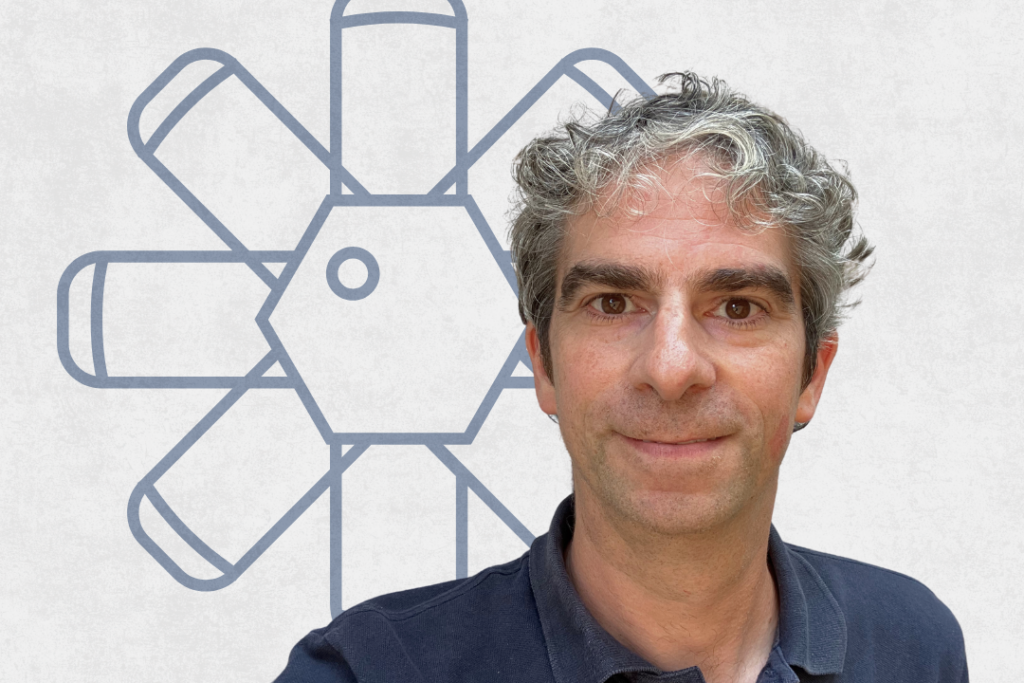

When the traffic lights in a major city stop working, people panic. But for Jordan Melzer, the real problems start years earlier – when the standards, software and systems that these devices use are designed. As a Catalyst Industry Fellow & Senior Engineer of Technology Strategy at TELUS, Dr. Melzer is focused on understanding the deeper challenges of the Internet of Things (IoT) and how to build fail-safes and responsibility into smart infrastructure.

Rethinking what ‘smart’ really means

IoT has become a buzzword, but often, the meaning beneath the word remains mysterious. Dr. Melzer clears this up simply. There’s a difference, explains Dr. Melzer, between a computer or a smartphone, which you can manage, and a device where you don’t control what it’s doing, at least not in a technical way. So the questions become, who’s responsible for it? How does it get new software? Who notices when it’s not working right?

Digital devices in the real world

Now, how can you determine the difference between your cellular device and IoT? Jordan says that these devices tend to perform actions or sense changes in the real world. They may measure your water usage, control the temperature inside a building, or help the city run its roads. “They interact with the real world,” says Jordan, and if they do something wrong, it can have potentially real-world consequences.

We can take these processes for granted, assuming that the railroad gate just lifts or the traffic light just changes. As Jordan jokes, railroads don’t work the old-fashioned way with a cartoon figure heaving on a heavy lever. Not only are many industrial and municipal processes increasingly remotely controlled, but this is also more often the case inside our homes.

The twin problems: abuse and neglect

He outlines two problems: abuse and neglect. Abuse — given the newsreel — is probably what comes to mind first and includes hackers, fraudsters, and ransomware. The concern with abuse is that people will try to break into things, then they will cause damage or threaten to cause damage, and that creates a massive problem at the national level. “We think of all the public infrastructure that is not so well guarded and definitely not secret. It really leaves the sense that anything could be vulnerable,” he says.

But then, there’s the neglect angle. Physical infrastructure may be in place for decades. Software is rarely maintained for a decade. The concern is that you put something secure and functioning in place, and a decade from now, the records are gone, it’s no longer receiving security updates and the security or even functionality is compromised. Without money to replace this infrastructure, it becomes a public problem.

A missing piece in IoT security

This is where Jordan’s work leading him to the Catalyst began. He wanted to examine how we could protect these devices, and what good practices should be put in place. He wondered, if the devices themselves aren’t very good, can we use the network to protect them? Dr. Melzer began working to solve this problem with partners in Canada and around the world in 2018. The focus was on home IoT devices, aiming to sort out how the devices could be better protected through good practices and network protections. New cybersecurity solutions were developed, but there was one untouched investigation, and that was the physical part. How could you encourage an IoT device to do the right thing, physically, and not cause harm? Dr. Melzer brought that problem with him to the Catalyst.

Bringing the problem to the Catalyst

“I wanted to look at the problem with fresh eyes,” says Jordan. He matched with two students — Sahil Bhatt and Reyhan Emik — and together, they are tackling the problem of whether good devices can do bad things. The concern is not about getting hacked, but instead that a device that has not been compromised may be told to do – and agree to go and do – something it shouldn’t do.

This problem is new because we only need to worry about what smart devices are saying to each other or what harm they may do when we have many smart devices. Within the Catalyst, Dr. Melzer is developing an approach that is drawn from endpoint security. He gives the example of a laptop. In an organization, there are some limits (imposed by an IT administrator) to what a user can do. Similarly, these limits should be put on objects of the Internet of Things. The starting point for such limits are models. As Dr. Melzer explains, for many of these devices, if you want them to do something, you have to model what that possible behavior is, so there need to be data models for each device. These models have rich descriptions, and when a system wants the device to do something, it uses that description and tells the model to do A or B.

Experimenting with Matter

The aim of Jordan’s Catalyst Fellowship project is to enhance those data models to include more context. This means including defaults and limits set by an administrator. These allow users or other smart devices to change settings with less risk of causing harm. To prove out and develop this concept, Dr. Melzer and his team needed a testing ground.

Matter is an industry standard for connecting smart devices. There are Matter data models for almost 100 device types: everything from lighting and heating controls to security and environmental sensors to cooktops and car chargers. If you look at Matter more closely, these data models are themselves broken down into smaller clusters that may be part of many device models. Rich data models allow many home components to be tied together into systems for heating, cooling, lighting, security, cleaning, charging, etc. that can respond to both changing user preferences and changes in the environment.

Dr. Melzer and his team wanted to see if administrative limits could be applied to these models. They asked some key questions: Were any limits in place already? What scenarios could they address? How could the team enrich these models to include more complex limitations? They have found administrative limits already in place in Matter’s thermostat model but in few other models. They have also developed a method to allow limits that respond to temporary conditions – like the home being empty or a power failure.

As he looks to conclude his fellowship, Jordan is thinking about, in his words, “What is drawing people to work on these solutions? Who is going to feel that they want to run with these ideas? Who is going to feel that these ideas are necessary enough to implement?” These questions will guide what he and his team do with their results.

Impact of the Catalyst Fellowship

“There are three things that the Catalyst offers from my perspective,” says Jordan. “One is community, including the other fellows. Another one, that is related to community, is having the support of TMU staff and the student team that works on the project. And finally, when you sign up, there’s a commitment. You’re choosing to spend a certain amount of energy on this problem instead of on something else, and I think all of those are important because without dedicated time and resources, not much happens.” He takes a step back and considers the cohort as a whole.

He reflects on his Fellow peers, first of which is Jordan Shaw-Young, who is examining how startups decide to invest in cybersecurity. Startups, Dr. Melzer says, are resource-starved groups. So, while they may be technically savvy enough to implement cybersecurity measures, the question is: do they see the real return and urgency? That’s one aspect of the cybersecurity problem, he says.

On an entirely different perspective is Jasbir Kooner, a graduate of Catalyst’s Mastercard Emerging Leaders Program (ELCI) whose work centred on bringing women into the conversation in cybersecurity. “We’re between the glass ceilings and the sticky floors,” says Jasbir. The list of Fellows and crucial topics goes on. “You have all these people grappling, as a whole, to find the reason to be engaged in cyber,” says Jordan.

What’s next for the Fellowship?

Does this year’s Catalyst fellowship cohort address the most pressing issues in cybersecurity today? Dr. Melzer says there are missing pieces, of course. Nobody is looking at national-level adversaries, he says, or addressing ransomware. But he acknowledges that no cohort could address every single issue. Dr. Melzer doesn’t expect one fellowship term to solve the whole problem — but the more people ask the right questions, the safer the future becomes. “That’s ample reason,” he says, “to run another Fellowship next year, and the year after, and the year after that.”

Want to join the Catalyst Fellowship Program?

Selected from academics at Canadian Universities and professionals working in a wide variety of organizations and sectors, Catalyst Fellows will undertake original research and other projects related to the Catalyst’s work; engage closely with Catalyst program participants and staff; and share their expertise in an environment dedicated to innovation and collaboration in cybersecurity.

There are two streams in the Catalyst Fellowship Program: the Industry Stream and the Academic Stream.

Application deadline: May 18. Click to apply: Catalyst Fellowship Program Brochure